Passing through Paris

Some notes on my exile and leaving America.

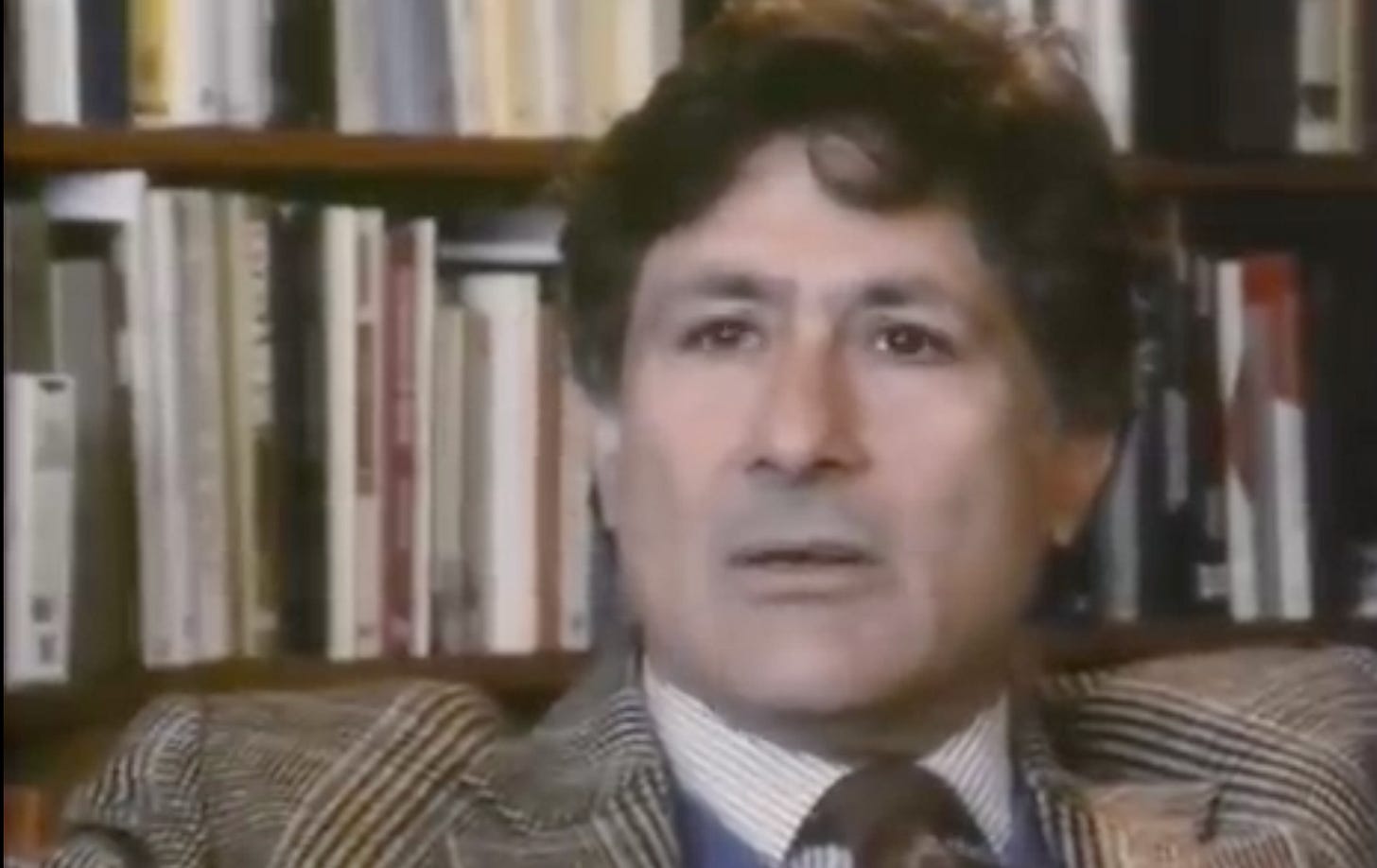

In memory of Edward Said, Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York, passed peacefully in 2003.

An American tourist protests the rough treatment of Palestinians by Israeli Border Control, 1987.

“Where should the birds fly after the last sky?”

- Mahmoud Darwish

I write these words from a bus which will shortly take me from London to Paris. The sun above is pale, wan and takes only perfunctory interest in me. The milky-cold gaze dares me to look it in the eye.

It is difficult for me to relay to you the personal vicissitudes that have all at once arranged things in such a way for me to be taking what has by now become a strangely familiar passage in my life, across the Channel, up over the Ferry or down through the Tunnel it’s all the same really, from capital city to capital city: light work, really, all in less than day’s work.

Seated uncomfortably close to an old man in a wide brimmed hat who says to me in an untraceable accent that my belongings are spilling everywhere, and carries on in this manner, pointing to the oranges bouncing out of my purse, the stolen one with the big metal cross and interlocking chains, bright pink in a shade reminiscent of a ballerina in stripper heels, the heavy books, the orange peels, the small catastrophe around me, the minor spectacle I have made of myself. I could list more, and will do so here: the quixotic struggle to zip up my backpack, the straps that come undone, bemused laughter, lurching forward with the vehicle’s movements, lurching suddenly, spilling again, spilling over, the futility of coherence.

He is still talking, somehow, still giving his view, and now he is berating me, chastising me in that blandly disinterested way. It is as if he has been sent by some force beyond that finds me worthy of condemnation: he is a grey fat fly that will not leave me alone, pursued to the ends of the Earth. It occurs to me on this bus that I am in exile. It occurs to me that I will be in exile for the rest of my life.

Edward Said, in an interview given to British television in 1987, says that exile can be thought, of course, as the interruption and lack of continuity that erupts from constantly having to move from one temporary location to the next. It is catastrophic, of course. It is loss. Remaining completely still, in the simultaneously effusively warm and tightly composed manner of insisting that would characterize his public appearances in Western media, he goes on to offer that there is, nonetheless, another way to think exile, to think in exile, to think through exile:

Since exile is a permanent state from which you cannot come back ….it is like the Fall, you can’t come back….what does exile afford you? …..the essential privilege of exile is to have not just one set of eyes but half a dozen, of all the places you’ve been.

Holding the camera’s gaze with a smile, Edward Said goes on to say:

As you’re looking at it now you’re remembering what it would have been like to look at something similar in the place from which you’ve come….always a double-ness to the experience… the more places the more composite and complex and interesting.

Looking ever-forward, the smile reaches his eyes this time.

His words bring to my mind Glissant’s concept of Relation, a knowing-oneself through the opacity of self and other, a boat on fearsome waves we sail for everyone, knowing me for knowing you, through an intense curiosity directed to everywhere, everyone you and I have been. Four years ago I read Poetics of Relation and let these wash over me on a beach in Puerto Rico. I ran back to my mother, excited to tell her that I’ve decided on a topic for my senior thesis. Philology meets poetics. Theory will save me!

I am writing more often these days. In my memories the East meets West. Coptic merchants and Al-Azhar learned men salute the dark skinned sailors of the New World and Edward Said saves the both of us a smile.

I am still, still sitting on the bus, my laptop is perched insecurely on my lap, over my felt-brown coat, Tommy Hilfiger golf vest (also stolen) and scattered array of wires, I am now watching a documentary about the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1987, remembering similar broadcasts I would watch of the situation in Gaza on my parent’s television in Cairo, Egypt. My mind drifts to Arabian horses galloping on the banks of the Nile and disappeared journalists on the run.

On my laptop screen the actions of the Israeli government are referred to by the British News Broadcast as the Battle of the Camps, a moniker which itself seems almost to grin with the sadistic irony and perverted gallows humor of the victorious one who imagines himself to be the ruler and final decider of not just the victim’s fate, but of reality itself. The self crowned final semiotic authority. The stamp of Truth with a capital T, pressed onto a Palestinian passport before it is ripped into pieces in front of the astonished bride, duly informed that she is now to travel on her husband’s passport while her place is given to a new settler family.

For of course, as the Palestinians and we as their witness are only too painstakingly aware, there is no conflict, it is not a war between two adversaries, it is men in uniforms marching an expelled people to their deaths. The refugee camps whose very existence have, apparently, provoked an uninterrupted hell of extermination by the IDF, an eternity of humiliation, of torture, of indignity, are encircled on all side by gunfire.

It is not enough that they were expelled from Palestine, they will be hunted in Lebanon, hunted in the refugee camps, set out to sea by the dozen in wooden boats and finally hunted to the ends of the Earth.

And this war, this “battle of the camps” is waged of course in the name of the ghoulish shadows of Hitler’s camps in Europe. These camps of extermination are transmuted by the magic powers of settler-colonialism into weapons themselves, from the traumatic memory of a generation of Jewish peoples in Europe, hunted themselves by Fascist bloodhounds, the very same death-camps have since been transformed by zionist ideology and western imperial designs into the proud emblems of war on the holy land. The camps transform into a mobilized army of reproducible totemic tokens to be held aloft by the occupying army as processional objects.

With brutal efficacy, they carry the water of a genocidal government, an exterminationist entity. This time, the entity murders Palestinian children in their beds for the glory of History.

The holocaust museum is paid for in acres of olive trees burned to ash.

It doesn’t bear repeating, to repeat it is unbearable, but look look look look here its is repeated, it is repeated, never again is not a prohibition only a transmutation of victims.

I am given an apology by the man sitting next to me. All is good, he says. I nod curtly in reply. The chess game app on his phone announces BRUTAL QUEEN VICTORY. My own buzzes with a text invitation for a funerary service and prayer devoted to Palestinians And Migrants.

On the border between the United Kingdom and France I am swaggering arrogant-school-boy-style. I am the chicest of exiles. Inside my jacket my hands are trembling and I need to be strong for the others.

Paris, at last.

City of exiles and of the irretrievable past, Paris of memory, the way it gleams and shines in so many diaphanous rays, the draped fabrics and balconies and lattice lace that together emerge out of so many French windows to adorn the corners of my eyes. Recalcitrant city of my memories.

It is already somewhere else. I am already on the way elsewhere to another city. Foot-fall down the path and up the stairs, I will buy flowers for the table. The air is different here. Europe is coolly indifferent to me. Landscape paintings on the night table, a piano playing Chopin in the next room, familiar faces, warm dots of light in the dark, dark, dark.

I look around, all around, through the eyes of all the places I have been.